In the heart of Kalol, Gujarat, where water scarcity casts a long shadow over daily life, one man’s journey embodies the spirit of innovation, determination, and environmental stewardship. Meet Mr. Amit Doshi, the visionary founder of NeeRain, a trailblazer in the realm of rainwater harvesting. His entrepreneurial voyage is not merely a story of success but a testament to the transformative power of dedication, ingenuity, and a deep-seated commitment to addressing pressing global challenges.

Amit’s narrative begins in Kalol, a town grappling with the relentless burden of water scarcity. Despite the adversities, he pursued his education with fervor, culminating in a Diploma in Plastic Engineering. These formative years instilled in him a profound understanding of the challenges faced by communities battling water shortages—a comprehension that would later fuel his entrepreneurial aspirations.

A pivotal moment came when Amit joined Sintex Industries Limited, marking the beginning of a remarkable 17-year journey. Rising through the ranks, he navigated diverse roles, from Production Supervisor to National Head for Environmental Enterprise. His tenure at Sintex honed his expertise in waste management, laying the groundwork for his future endeavors. However, Amit harbored a burning desire to chart a new path—one that would transcend the confines of traditional waste management and delve deeper into the realm of environmental sustainability.

In 2014, Amit took the leap of faith, bidding farewell to Sintex Industries to embark on his entrepreneurial odyssey. His mission was clear: to tackle water-related challenges head-on while revolutionizing the landscape of rainwater harvesting. Thus, NeeRain was born—a testament to his unwavering commitment to environmental stewardship.

At the core of NeeRain’s ethos lies a profound dedication to simplicity, accessibility, and effectiveness. Amit envisioned a solution that would democratize rainwater harvesting, making it accessible to all. The result? A groundbreaking innovation: rooftop rainwater filters designed to capture, purify, and store rainwater with unparalleled efficiency. Made from ABS plastic, these filters boast a dual-stage filtration process, ensuring the purity of collected water. What sets NeeRain apart is its affordability, ease of installation, and low maintenance—a stark departure from traditional methods plagued by complexity and high costs.

The inspiration behind the name “NeeRain” is as poetic as it is profound. Rooted in Sanskrit, “नीर” (Neer) translates to water, symbolizing the essence of life itself. Paired with “Rain,” the name embodies the company’s mission to harness the life-giving power of rainwater for the greater good—a mission encapsulated by the mantra Amit lives by: “Contribute more, expect less.”

NeeRain’s journey has been marked by remarkable milestones, including prestigious awards and recognition for its contributions and innovative products:

- Won CII’s National Award for Excellence in Water Management 2022 in the innovative water-saving product category.

- Featured in the first episode of the series “ChangeMakers“ by Doordarshan.

- Signed an MOU with the WASH Innovation Hub, Government of Telangana, for upcoming rainwater harvesting projects.

- Engaged by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development for projects at Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation worth Rs. 20 Lakhs.

- Mentioned in the coffee table book of CII.

- Attained global recognition by The Better India.

- Article published by Partho Burman.

- Awarded the Water Leadership Award by The Economic Times Group.

- Acknowledged as an Emerging Startup in water conservation by the Entrepreneurship Development Institution of India.

Photo Courtesy : CEO VINE

In its initial stages, NeeRain received a significant CSR grant of Rs. 10.81 lakhs from HDFC Bank through Cradle, EDII, which served as a catalyst for the company’s growth. Today, NeeRain’s revenue is poised to reach approximately Rs. 2 crore, a testament to its burgeoning success and impact in the field of water management.

- Yet, for Amit, success transcends mere accolades and revenue figures. It is rooted in a profound sense of purpose—a commitment to empowering individuals, communities, and the planet. In his spare time, Amit channels his passion for empowerment through motivational videosaimed at inspiring the next generation of changemakers.

- Aspiring entrepreneurs seeking to follow in Amit’s footsteps are met with sage advice: identify real problems, devise affordable solutions, and embrace simplicity and scalability. The journey may be fraught with challenges, but with perseverance and innovation, transformative change is within reach.

- In the annals of entrepreneurship, Amit Doshi’s story stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of human ingenuity—a beacon of hope in an ever-changing world. Through NeeRain, he has not only revolutionized rainwater harvesting but also ignited a movement—one that empowers individuals to shape a more sustainable future for generations to come.

NeeRain is proud to republish this blog to spread awareness about the situation of water, for our stakeholders. Credit whatsoever goes to the Author.

This blog is published by:

CEO VINE

We would like to spread this for the benefit of fellow Indians.

Author : Rosalin

Published On : 1 March, 2024

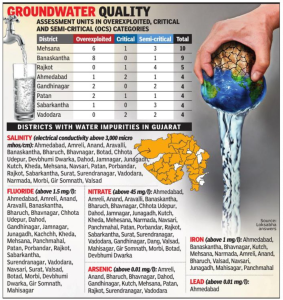

Photo Courtesy : Deccan Chronicle

Photo Courtesy : Deccan Chronicle

Photo courtesy: https://blog.nextias.com/water-crisis-a-complete-picture

Photo courtesy: https://blog.nextias.com/water-crisis-a-complete-picture Photo courtesy:istock

Photo courtesy:istock