Photo Courtesy : The Hindu

UDAIPUR: Capturing rainwater is the most sustainable solution to deal with water scarcity in Rajasthan and specially when the technique is the traditional wisdom of the desert state.

According to Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), out of 243 blocks in Rajasthan, 196 fall in the critical zone. This means that in these regions, the annual withdrawal of water from underground is more than what falls as rain. There is growing imbalance between demand and supply of water in the state.

As per international standards, availability of water below 500 cubic meter is considered as absolute water scarcity. The annual per capita availability of water in the state is expected to go down to 439 m3 by 2050 which was 840 m3 in 2001 and against the national average of 1,140 m3 by 2050. Wells for India, (WI) a UK-based NGO which have been working for three decades for the water cause, has helped people to deal with water scarcity through rainwater capturing techniques. WI with its partner GRAVIS, another NGO helped construction and repair of 895 taankas in Pabupura cluster in the Phalodi block of Jodhpur district which has ensured water security to 900 families. These Taankas have of 21,000 litre capacity.

Now 900 families have water source at their doorstep for a period varying from 9 to 12 months. “The intervention has helped women in saving time, money and labour. Their working hours have reduced from 18 to 15 hours and now they can relax for around nine hours a day as compared six hours in the past. The increased water availability for a longer duration has reduced physical workload, mental stress and health related problems of women,” says OP Sharma, country director, WI.

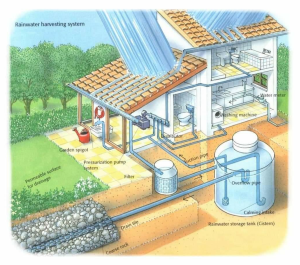

Photo Courtesy : engineering and architecture

Tanka beneficiaries started to take bath and wash clothes more frequently. The water use in washing clothes and taking bath has increased by more than 4 times, whereas the water used by animals has increased by 2.5 times. Moreover, daily cleaning of utensils and water storage pots has substantially increased. Above 70% of the tanka families have started using alum/chlorine tablets to purify their drinking water, whereas more than 80% of the families have started using ladle to take water from the pot. Last but not least, expenditure incurred on water for drinking and domestic purpose including the water for animals reduced from 2 to 3 times.

Similarly in Hilly regions of Bhinder block of Udaipur seen the significant impacton increase in irrigated area on account of mainly ground water / well rechargedue to construction of small water harvesting works such as loose stone checkdams, masonry dams etc. Prior to construction of these structures the totalirrigated area under the command of these 39 existing wells (i.e in 2004) was only 23 hectare, which has now been (up to Rabi 2016 ) increased to 80 hectare. Irrigated area is showing the significant impact of these small water harvesting works on increasing the availability of water.

NeeRain is proud to republish this blog to spread awareness about the situation of water, for our stakeholders. Credit whatsoever goes to the Author.

This blog is published by:

Times Of India

We would like to spread this for the benefit of fellow Indians.

Author : Times Of India

Published On : 22 Mar, 2017

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Down to earth

Photo courtesy: Down to earth Photo courtesy: Anand Rko

Photo courtesy: Anand Rko Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat

Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.

Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.

Photo credit: Venngage Inc

Photo credit: Venngage Inc Photo courtesy: RCH/Fotolia

Photo courtesy: RCH/Fotolia Photo courtesy:

Photo courtesy:  Photo courtesy: Adobe stock

Photo courtesy: Adobe stock Photo courtesy: Shutterstock

Photo courtesy: Shutterstock Photo credit: Shutterstock

Photo credit: Shutterstock Photo credit: Pinterest

Photo credit: Pinterest Photo credit: Vecteezy

Photo credit: Vecteezy