The villagers surprised the government and administration by refusing to get a borewell constructed in their village.

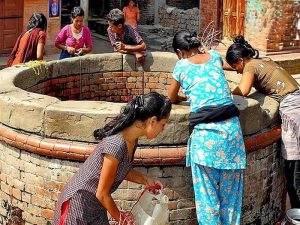

Villagers digging wells in Kedia village of Jamui district of Bihar. Photo: Pushyamitra

Villagers digging wells in Kedia village of Jamui district of Bihar. Photo: Pushyamitra

Pushyamitra

There is a festive atmosphere these days in Kedia village of Jamui district of Bihar. Digging of wells is going on in full swing. 16 wells are to be dug in this only organic village of Bihar. Till now two wells have been completely ready, excavation of the remaining wells is going on. The villagers acquired these wells by fighting with the government. The government wanted to provide them the facility of two state borings, but they said that they only want wells. The underground water level will fall due to boring, some people will get immediate benefit from this, the rest will be deprived. The Bihar government had to bow down to the insistence of the villagers and give permission for the digging of sixteen wells in this village.

Anandi Yadav, a farmer of the village, says, it all started three years ago when Sudhir Kumar, Principal Secretary of the Agriculture Department, came to visit the village. By that time the village had completely adopted organic farming and the Principal Secretary was very happy about this. He had said at that time that when you people are doing so much work then why not give you two state borings for irrigation from the government. But the Principal Secretary was surprised when the people of the village unanimously opposed the state boring and said that if we have to give something then we should give the wells.

After this, a survey of the farmers of the village was conducted and most of the farmers agreed in favor of wells, however, during the survey, some farmers said yes to state boring and the district administration, considering the opinion of those farmers, is preparing to install state boring in Kedia village. Started doing. When the villagers came to know about this, they opposed this plan and gave a written application to the district administration and the state agriculture department that a well should be dug in the village and not a state boring.

After this, when State Agriculture Minister Prem Kumar also came to this village, people told him this. However, even after this the work was not done easily. He had to keep requesting the state government and the district administration. Only then was approval given for 16 wells for the village.

Photo courtesy: villagesquare.in

Photo courtesy: villagesquare.in

Today, when wells are being dug in the village, the villagers are very happy. Farmer Sumant Kumar says that ever since organic farming has started in the village, our attitude towards farming has changed. By forming an organization called Jeevit Mati Kisan Samiti, we continuously do new experiments in farming so that the quality of the soil is preserved and our farming can become sustainable. He says that the most interesting thing is that Jamui is considered a water stressed area in Bihar and the water level here is the lowest. But when we are digging wells, water is coming out only at a depth of 17 to 22 feet. We are finding it difficult to collect water.

On Thursday, June 13, State Agriculture Minister Prem Kumar is going to reach Kedia village to lay the foundation stone of these wells. Interestingly, the farmers of the village have also donated 80 decimal land to the state government for these wells at the rate of 5 decimal land per well.

Ishtiaq Ahmed, associated with the organic farming campaign, says that for water conservation, it is very important to conserve soil and increase the amount of organic carbon in it. In this respect, this experiment has its own importance and it is expected that farmers across the state will adopt it. This will help in better conservation of soil and water.

Eklavya Prasad, who is engaged in developing water self-reliance in Bihar through the Megh Pine campaign, says that the way the farmer community has been accepted in Kedia is a big achievement in itself, because the well is the ideal of irrigation with self-management and regulation. The means are there, if anything happens to the well tomorrow, the farmers will not depend on anyone, they can repair it themselves. Under this pretext, the good thinking of the farmers there is also coming to the fore. If the government is digging 16 wells instead of 3-4, then it is also an initiative to promote decentralization, in this respect this decision of the government is also excellent. If water is available there at 17 to 22 feet, then obviously we need to think again about the wells and adopt it. This is positive news not just for Kedia but for entire Bihar. If this campaign is carried forward in a concrete manner then its results will be excellent.

Sanjay Kumar, Deputy Director, Planning and Soil Conservation, State Agriculture Department, calls this experiment very important and says that even though today farmers have to do irrigation through boring, sooner or later the farmers of the state will adopt this model.

Neerain is proud to republish this blog for spreading awareness about situation of water, for our stake holders. Credit whatsoever goes to the Author.

This blog is published by: –

We would like to spread this for the benefit of fellow Indians.

Publish On: 11 June 2019

Photo courtesy: down to earth

Photo courtesy: down to earth Photo courtesy: pinterest

Photo courtesy: pinterest Photo courtesy: wordpress.com

Photo courtesy: wordpress.com Photo courtesy:Neerain

Photo courtesy:Neerain Photo courtesy:Istock

Photo courtesy:Istock

Photo courtesy: Santhosh Kumar

Photo courtesy: Santhosh Kumar Photo courtesy:Shuttterstocks

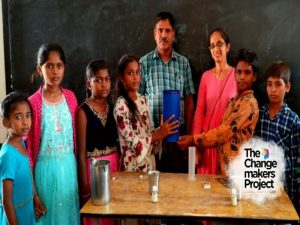

Photo courtesy:Shuttterstocks With the onset of the monsoon season, Government Model Higher Primary School in Kora village in Tumakuru has been capturing every drop of rain that fell from the sky. All photos by arrangement.

With the onset of the monsoon season, Government Model Higher Primary School in Kora village in Tumakuru has been capturing every drop of rain that fell from the sky. All photos by arrangement. Rao has been raising awareness about various environmental issues, including water conservation, here, he is explaining his students about the rainwater harvesting system.

Rao has been raising awareness about various environmental issues, including water conservation, here, he is explaining his students about the rainwater harvesting system. Explaining how the rainwater harvesting system at the school works, Shivananda R S, a team leader at Biome, said: “We calculate sump [storage tank] capacity based on the rooftop area available for harvesting. The first one millimetre of rainwater which washes the terrace is let out through the first rain separator controlled by a valve.”

Explaining how the rainwater harvesting system at the school works, Shivananda R S, a team leader at Biome, said: “We calculate sump [storage tank] capacity based on the rooftop area available for harvesting. The first one millimetre of rainwater which washes the terrace is let out through the first rain separator controlled by a valve.” According to Shivananda, the school harvests 560 kilo litres (KL) of water out of which 280 KL is stored and reused, and 280 KL is recharged annually.

According to Shivananda, the school harvests 560 kilo litres (KL) of water out of which 280 KL is stored and reused, and 280 KL is recharged annually. “When the plant was being set up, we were told about rainwater harvesting and how it had huge advantages. Rao Sir told us how it was important to conserve water and not squander it so that we could avoid a water crisis in the future,” Sandhya Rani, a 13-year-old student of class 7 told Gaon Connection.

“When the plant was being set up, we were told about rainwater harvesting and how it had huge advantages. Rao Sir told us how it was important to conserve water and not squander it so that we could avoid a water crisis in the future,” Sandhya Rani, a 13-year-old student of class 7 told Gaon Connection. Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images Photo courtesy: AKHILESH YADAV

Photo courtesy: AKHILESH YADAV Photo courtesy: Down to earth

Photo courtesy: Down to earth Photo courtesy: Anand Rko

Photo courtesy: Anand Rko Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat

Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.

Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.