The government school in Kora village in Tumakuru has enough water for drinking, cooking, washing and gardening purposes thanks to the rainwater harvesting system installed with the help of the non-profit Biome.

With the onset of the monsoon season, Government Model Higher Primary School in Kora village in Tumakuru has been capturing every drop of rain that fell from the sky. All photos by arrangement.

With the onset of the monsoon season, Government Model Higher Primary School in Kora village in Tumakuru has been capturing every drop of rain that fell from the sky. All photos by arrangement.

Water situation in Karnataka is worrisome as several districts in the state have received deficient rainfall in the southwest monsoon season that ended last month. The region of south interior Karnataka is particularly affected, and sharing of Cauvery river’s water between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu has become a hot topic for dharna and protests.

But a village school in Tumakuru district in rain-deficient south interior region of Karnataka is not worried about the looming water crisis.

The government school has enough water for drinking, washing and gardening purposes. And the water — harvested rainwater — has been a ‘free’ gift from the heavens above.

Since June this year, with the onset of the monsoon season, Government Model Higher Primary School in Kora village in Tumakuru has been capturing every drop of rain that fell from the sky on the school premises located over 70 kilometres from the state capital Bengaluru.

Today, the rural school with 208 children studying in classes one to seven has sufficient water to use for its cooking, gardening, cleaning and drinking purposes. For drinking and cooking, the harvested rainwater is filtered with the help of RO (reverse osmosis) so that it is clean and safe to drink for the students and staff.

Also Read: Gaon Connection Launches ‘The Changemakers Project’ to Build a National Registry of Changemakers

The credit for making the school self-sufficient in water goes to Madhusudan Rao, headmaster at the school, who thought up a plan to capture, store, treat and use rainwater in his school. In a changing climate, with rainfall patterns changing, harvesting every drop of rainwater that falls on the ground is the need of the hour.

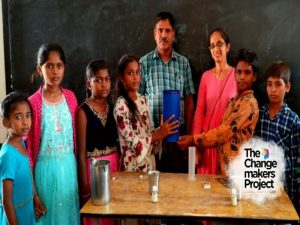

Rao has been raising awareness about various environmental issues, including water conservation, here, he is explaining his students about the rainwater harvesting system.

Rao has been raising awareness about various environmental issues, including water conservation, here, he is explaining his students about the rainwater harvesting system.

“I wanted to set up a rainwater harvesting system in the school. It made so much sense because it is cost effective, and promotes both water and energy conservation,” the 57-year-old headmaster told Gaon Connection.

Rao has taught for 33 years and is actively involved in the People Science Movement that popularises science and scientific outlook amongst people. He also volunteers at the Tumkur Science Centre where he raises awareness about various environmental issues, including water conservation.

To execute the rainwater harvesting plan at his school, the headmaster got in touch with Bengaluru-based Biome Environmental Solutions, which works on ecological architecture and intelligent water and sanitation designs. Biome’s rainwater harvesting work is supported by Wipro Cares, an employee-led community initiative arm of the Wipro Foundation.

Also Read: Harvesting rainwater saves the day for residents of a tribal village in Jharkhand

“First of all with the help of Biome, we identified our catchment area to capture rainwater and then started digging to collect raindrops that fall within our school premises. We now have one tank, which has the capacity of 19,250 litres, and stores rainwater,” explained Rao. This much water can meet the school’s water needs for two months.

Explaining how the rainwater harvesting system at the school works, Shivananda R S, a team leader at Biome, said: “We calculate sump [storage tank] capacity based on the rooftop area available for harvesting. The first one millimetre of rainwater which washes the terrace is let out through the first rain separator controlled by a valve.”

Explaining how the rainwater harvesting system at the school works, Shivananda R S, a team leader at Biome, said: “We calculate sump [storage tank] capacity based on the rooftop area available for harvesting. The first one millimetre of rainwater which washes the terrace is let out through the first rain separator controlled by a valve.”

“Afterwards the cleaner water is passed through a masonry or wall mounted filter and stored in a rainwater sump. The stored rainwater is then pumped to an overhead tank and reused,” he added.

The rainwater harvesting system was installed in June this year. By the end of August, there was enough water for the school to use for its cooking, gardening, cleaning and drinking purposes. The water is filtered before using for drinking purposes.

According to Shivananda, the school harvests 560 kilo litres (KL) of water out of which 280 KL is stored and reused, and 280 KL is recharged annually.

According to Shivananda, the school harvests 560 kilo litres (KL) of water out of which 280 KL is stored and reused, and 280 KL is recharged annually.

The entire project of installing the rainwater harvesting system in school has been a learning process for the students too. Headmaster Rao ensured that the students watched and participated in the installation of the system.

“When the plant was being set up, we were told about rainwater harvesting and how it had huge advantages. Rao Sir told us how it was important to conserve water and not squander it so that we could avoid a water crisis in the future,” Sandhya Rani, a 13-year-old student of class 7 told Gaon Connection.

“When the plant was being set up, we were told about rainwater harvesting and how it had huge advantages. Rao Sir told us how it was important to conserve water and not squander it so that we could avoid a water crisis in the future,” Sandhya Rani, a 13-year-old student of class 7 told Gaon Connection.

“We learnt how water can be reused for our day-to-day activities such as flushing of toilets, cleaning, gardening and cooking,” she added.

According to Shivananda, the harvested rainwater will not be able to meet the school’s water needs throughout the year, but can take care of its water requirements to a great extent. This means reducing dependence on external sources of water, such as borewells that exploit groundwater, or tankers that source water from far.

Every drop counts, as rainwater harvesting experts often point out.

Also Read: In these villages in Jaisalmer, every house has a traditional ‘beri’ to collect rainwater

Biome has been working with four schools to promote rainwater harvesting. Of these, the rainwater harvesting system is already functional in three schools and is under construction in the fourth school. The non-profit designs rainwater harvesting with inputs from schools and involves the students, teachers, and School Development and Monitoring Committee members.

“We also conduct water literacy activities in the school. We give children water quality kits, rain gauges to measure rainfall, setting up vegetable and fruit gardens, etc. We also handhold the school by maintaining the rainwater harvesting system for at least a year, till the school can function on its own without us,” said Shivananda.

Neerain is proud to republish this article for spreading awareness about situation of water, for our stakeholders. Credit whatsoever goes to the Author.

This article is published by: –

Author: Laraib Fatima warsi

Publish On: 10 / Oct / 2023

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Photo courtesy: Getty Images Photo courtesy: AKHILESH YADAV

Photo courtesy: AKHILESH YADAV Photo courtesy: Down to earth

Photo courtesy: Down to earth Photo courtesy: Anand Rko

Photo courtesy: Anand Rko Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat

Photo courtesy: Muench/Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA) Secretariat Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.

Photo courtesy:Akruti Enviro Solutions Pvt.Ltd.

Photo credit: Venngage Inc

Photo credit: Venngage Inc Photo: iStock

Photo: iStock Photo credit: istock

Photo credit: istock Depletion of groundwater

Depletion of groundwater Uneven distribution

Uneven distribution Contamination and pollution

Contamination and pollution Rainwater harvesting also helps in reducing India’s dependence on groundwater and private sources like tankers.

Rainwater harvesting also helps in reducing India’s dependence on groundwater and private sources like tankers. Photo Courtesy: Statustown

Photo Courtesy: Statustown